Moreover, climate change influencing gold’s role in central bank reserves is becoming a central topic for students, policymakers, and finance professionals alike. Furthermore, this phrase — Climate Change Influencing Gold’s Role in Central Bank Reserves — captures three overlapping shifts: first, the macroeconomic and geopolitical drivers that push central banks toward gold; second, the climate-related risks and sustainability concerns attached to gold as a physical commodity; and third, the institutional responses by central banks that now must reconcile reserve management with climate risk frameworks. Consequently, understanding this topic helps students link environmental science, monetary policy, and portfolio management in a practical, policy-relevant way.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy Gold Has Long Been Central to Reserves — and Why That’s Changing

Firstly, gold has historically been valued by central banks for three core reasons: as a store of value, as a volatility hedge (especially versus currencies), and as a shock absorber in times of geopolitical or financial stress. Secondly, in recent years central banks significantly increased gold purchases, responding to geopolitical uncertainty, currency diversification needs, and concerns about fiat currency risks. For example, surveys and statistics from the World Gold Council and regional authorities show record central-bank buying in the early 2020s, with continued strong appetite through 2024–2025.

However, while demand rose, another narrative emerged: gold is not only a financial asset but also a physical commodity whose production and supply chains have environmental footprints. Therefore, central bankers and analysts are increasingly asking whether gold in reserves creates exposure not only to market and liquidity risks but also to climate and ESG risks — both direct (environmental damage from mining) and indirect (reputational or transition risk as global policy and markets decarbonize).

The Two Sides of the Coin — Gold as a Climate Hedge vs Gold’s Environmental Footprint

Gold as a climate hedge and safe-haven (financial side)

Moreover, climate change can increase macroeconomic volatility — for instance, through extreme weather disrupting supply chains, or through the geopolitical fallout from resource stresses — and therefore can increase demand for safe-haven assets. Consequently, gold’s historical role as a diversifier and crisis hedge can become more valuable to central banks seeking resilience in the face of climate-driven shocks. In short, climate change can strengthen the financial case for holding gold.

Gold’s environmental footprint (physical side)

Conversely, gold mining is carbon- and resource-intensive. Nearly all greenhouse-gas emissions related to gold arise from mining operations and, primarily, electricity generation for mining activities. Studies estimate global GHG emissions from gold mining in excess of 100 million tonnes CO₂-e per year, while lifecycle assessments highlight large variance in emissions intensity across mines and countries. Hence, gold is not immune to environmental scrutiny.

Therefore, the physical realities of gold production — deforestation, water use, mercury pollution in artisanal operations, energy-intensive ore processing — create ESG and reputational risks. For central banks that now emphasize sustainability and the legal/regulatory dimensions of climate risk, holding a commodity tied to such impacts complicates the picture.

How Central Banks Are Responding — Integrating Climate Risk into Reserves Management

Firstly, central banks are not a monolith. Yet across many jurisdictions the trend is clear: financial authorities are moving to incorporate climate risk into their operational frameworks, guided by international studies and networks (for example NGFS), legal reviews (IMF work), and internal risk committees. Consequently, reserves management — long viewed as a technical, rule-driven function — is receiving new scrutiny for climate-related exposures.

Moreover, the responses take several concrete forms:

- Climate risk assessment for reserve assets. Some central banks are exploring how to measure climate exposure across asset classes, including the unique characteristics of physical commodities like gold. Academic and policy work has proposed frameworks to treat gold as a separate asset class in climate-risk analysis.

- Sustainability and ethical sourcing criteria. While central banks rarely buy newly-mined retail jewellery, their purchases can drive attention to traceability, responsible sourcing, and environmental standards in the mining supply chain. Accordingly, central banks and official-sector buyers are beginning to ask suppliers and market intermediaries about provenance and environmental credentials.

- Portfolio policy adjustments. In some cases, central banks are expanding diversification not to remove gold but to balance its role with green bonds, foreign-exchange diversification, and other assets that may align better with climate objectives. This is partly driven by guidance and recommendations from international working groups on sustainable reserve management.

Practical Issues — Liquidity, Valuation, and Climate Stress-Testing Gold

Moreover, integrating climate risk into reserve management raises several technical questions that students and practitioners must wrestle with, including liquidity, valuation, and stress-testing.

- Liquidity and market functioning. Gold benefits from deep, liquid markets (London, COMEX, Shanghai). Consequently, central banks can usually buy or sell gold without the same friction as some green instruments. However, sudden surges in demand — for example, during geopolitical crises or climate-induced economic shocks — can spike prices and market stress.

- Valuation under transition scenarios. If policy responses to climate change (e.g., carbon pricing, shifts away from fossil fuels) alter the value of currencies, commodities, and sovereign risk premia, the relative attractiveness and real returns of gold could change. Thus, valuation models used by reserve managers are being updated to include climate transition scenarios. Stress-testing and scenario analysis. Central banks already use stress tests for financial risk; now they must layer climate scenarios on top. For gold this means considering not only market shocks but also long-term supply impacts (e.g., mine closures due to water shortages or carbon costs), which could affect supply dynamics and price volatility. Academic work suggests methods for integrating gold into climate-stress frameworks.

Supply-Side Climate Vulnerabilities — How Climate Change Can Affect Gold Supply

Firstly, climate change is not just about emissions — it is also about physical risks (droughts, floods, heat) that affect mining operations. For example:

- Water stress and mine operations. Many gold-mining operations depend heavily on water for processing ores. Consequently, prolonged droughts or competing water uses (agriculture, domestic supply) can constrain production or increase costs.

- Extreme weather events. Flooding and storms can damage infrastructure and delay production or transportation, introducing supply shocks.

- Transition costs and carbon pricing. If regulatory frameworks impose carbon pricing or stricter environmental controls, the cost base for high-emissions mines can rise, potentially causing closures or consolidation in the sector. This can reduce supply or shift the supply mix toward regions with greener power grids. Studies have modelled the impact of carbon pricing on mining costs and profitability.

Therefore, students should note that supply-side shocks are real and can affect gold’s market dynamics — which in turn matters for reserves valuation and liquidity considerations.

Demand-Side Climate Effects — Why Climate Drivers Can Increase Centrals’ Appetite for Gold

Moreover, climate change can increase demand for gold via multiple channels:

Deepak Goyal CFA & FRM

Founder & CEO of RBei Classes

- 16,000+ Students Trained in CFA, FRM, Investment Banking & Financial Modelling

- 95% Students Successfully Placed • 94.6% Pass Rate In Exam

- Increased macro risk and currency instability. Climate shocks can produce macro instability in vulnerable countries, which could weaken currencies and incentivize central banks to hold assets perceived as reliable stores of value.

- Geopolitical and food/energy security shocks. Climate-driven resource stress can amplify geopolitical tensions, making safe-haven assets more attractive to official buyers.

- Portfolio resilience thinking. As central banks adopt a resilience mindset — balancing liquidity, security, and return while considering systemic risks — gold’s unique properties (liquid, non-sovereign, historically uncorrelated in crisis) can be emphasized. Evidence from central bank surveys indicates that many institutions continue to view gold as an important part of strategic reserves. Consequently, climate-related volatility can act as a tailwind for gold holdings, even as environmental considerations act as a headwind.

Reconciling the Paradox — How Central Banks Can Keep Gold While Meeting Climate Goals

Firstly, this section outlines practical, implementable approaches central banks might use to reconcile holding gold with climate responsibility.

1. Transparency and reporting on gold holdings and sourcing

Moreover, central banks could improve transparency on the provenance and chain-of-custody for gold purchases. Therefore, they can demand better reporting from bullion banks and refineries about the environmental standards of the mines that supply the gold they buy. Voluntary disclosure standards already exist within the industry, and central banks can signal preferences for responsibly sourced physical gold.

2. Preferential procurement and certified supply chains

Furthermore, central banks could prioritize buying gold that adheres to recognized certification programs (e.g., Responsible Gold standards, where available) or that is traceable to mines with lower greenhouse-gas intensity. Consequently, official-sector demand can incentivize greener mining practices by creating market advantages for lower-carbon producers.

3. Climate-adjusted reserve metrics

Additionally, reserve managers can develop metrics that incorporate climate-adjusted risk premiums or that stress-test portfolios under climate transition scenarios. Thus, gold’s allocation would be decided not only on historical correlations but also on forward-looking climate-adjusted scenarios. Academic frameworks and central bank guidance point toward such practice.

4. Engagement and policy influence

Finally, central banks can use their standing to encourage industry-wide decarbonization in mining (for instance, supporting renewable power in mining regions or endorsing financing for clean-up of artisanal operations), which over time reduces the environmental footprint of the asset class they hold. This is consistent with broader central-bank engagement on climate via supervisory or financial-stability channels.

Case Studies & Recent Evidence — What the Data Shows (Students’ Short Summary)

Firstly, students should take note of a few empirical findings that illustrate the dynamics discussed above:

- The World Gold Council’s 2025 Central Bank Gold Reserves survey reported sustained official-sector interest in gold and a high proportion of central banks planning to increase holdings. This demonstrates the continued strategic importance of gold in reserves management.

- The European Central Bank and other regional authorities have noted that gold accounted for a sizable share of demand in recent periods, and that market dynamics around gold have been influenced by macro and geopolitical stressors.

- Research shows significant greenhouse-gas emissions from gold mining globally (estimates in the order of 100 Mt CO₂-e annually), with major variability across operations — implying opportunities to reduce emissions through energy switching and efficiency.

- Policy guidance from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and IMF research indicates that central banks face legal, reputational, and financial considerations in integrating climate into financial policy — which naturally extends into reserves and asset choices.

Therefore, the evidence points to a continued strategic role for gold, but paired with rising expectations for central banks to manage climate-related aspects of that role.

Classroom Takeaway — How Students Should Think About This Topic

Firstly, if you are a student studying finance, environmental policy, or central banking, use this topic to connect multiple disciplines:

Moreover, combining these lenses will prepare you to advise policymakers or work in official-sector roles where multidisciplinary thinking is essential.

FAQs Students Ask (Quick Answers)

Will central banks stop buying gold because of climate concerns?

A — No, not imminently. Central bank buying has been strong and gold’s financial role remains valued. However, central banks may add climate-related conditions (traceability, supplier standards) or complement gold with green assets.

Can gold be “green”?

A — Partially. Mining can reduce emissions by switching to renewable power, adopting cleaner processing, and improving waste management. Therefore, lower-carbon or responsibly sourced gold is possible and is being discussed in industry research.

Does gold’s footprint matter for a central bank that just holds bars in vaults?

A — Yes, because central banks face reputational and policy scrutiny, and their procurement choices send market signals that affect mining practices and investor perceptions. Moreover, physical supply risks tied to environmental issues can affect market prices.

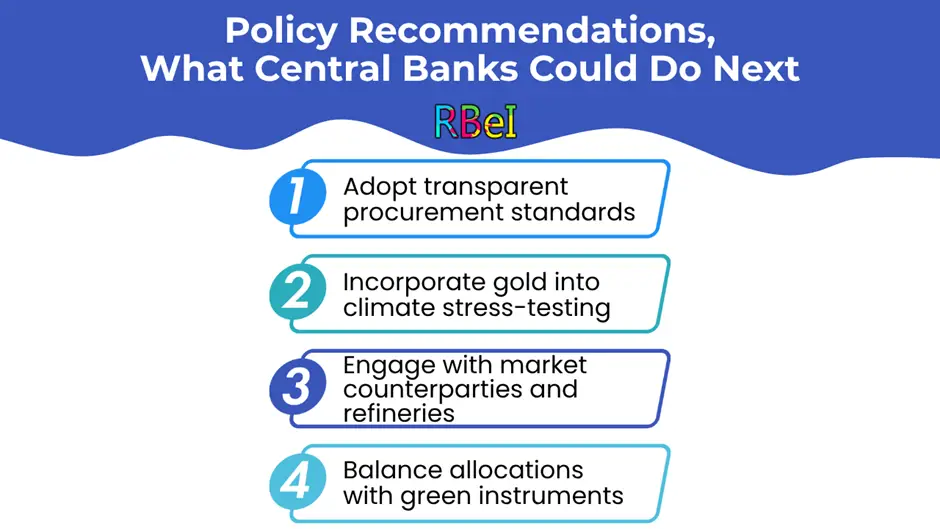

Policy Recommendations — What Central Banks Could Do Next

Firstly, synthesizing the analysis above, here are concrete recommendations central banks could adopt — useful as talking points for class debates or policy memos:

Consequently, these steps would allow central banks to retain the risk-mitigation benefits of gold while reducing environmental and reputational downsides.

Longer-Term Outlook — Where This Trend Could Lead

Moreover, looking forward, several plausible scenarios may emerge:

- Scenario 1 — Green Gold Transition. Mining firms decarbonize rapidly, certification standards emerge, and central-bank procurement favors low-carbon gold. Thus, gold’s role stabilizes and its environmental footprint declines.

- Scenario 2 — Diversification & New Safe Assets. Central banks diversify into new forms of safe assets (e.g., certain inflation-linked instruments, more diverse currency baskets, or highly liquid green instruments), causing a modest decline in gold allocations.

- Scenario 3 — Supply Shock Amplification. Climate impacts on mining (water stress, extreme weather) plus transition costs cause supply volatility, pushing gold prices higher and reinforcing its crisis-hedge role but increasing market volatility.

Therefore, students should track both market indicators (central bank purchases, ETF flows) and climate-policy signals (carbon pricing, mining regulation) to understand future allocation trends. Recent data show that central bank demand has been strong into 2024–2025 — but the long-term path depends on policy and industry responses.

Suggested Further Reading & Sources (Selected)

For your research papers or assignments, consult these authoritative sources:

- World Gold Council — Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey 2025 and ESG research on gold and climate.

- European Central Bank commentary and analyses on gold demand and macro implications.

- UNEP-FI and academic papers on climate risks in metals & mining. NGFS & IMF publications on central banks and climate integration.

These readings will give you both empirical data and policy frameworks to support essays, presentations, or project work.

Conclusion — Bringing It Together

Therefore, to conclude: Climate Change Influencing Gold’s Role in Central Bank Reserves is a multidimensional topic. Moreover, the paradox is clear — while climate shocks and geopolitical volatility can strengthen the financial case for gold as a reserve asset, the environmental footprint and supply vulnerabilities of gold mining create new policy, reputational, and risk-management challenges for central banks. Consequently, the path forward combines improved disclosure, procurement standards, climate-adjusted risk frameworks, and industry engagement. In the end, central banks can continue to use gold as a pillar of reserves, yet they must adapt reserve-management practices to the realities of a warming world.